DH 201: DH Project Evaluation with Jamie Gravell

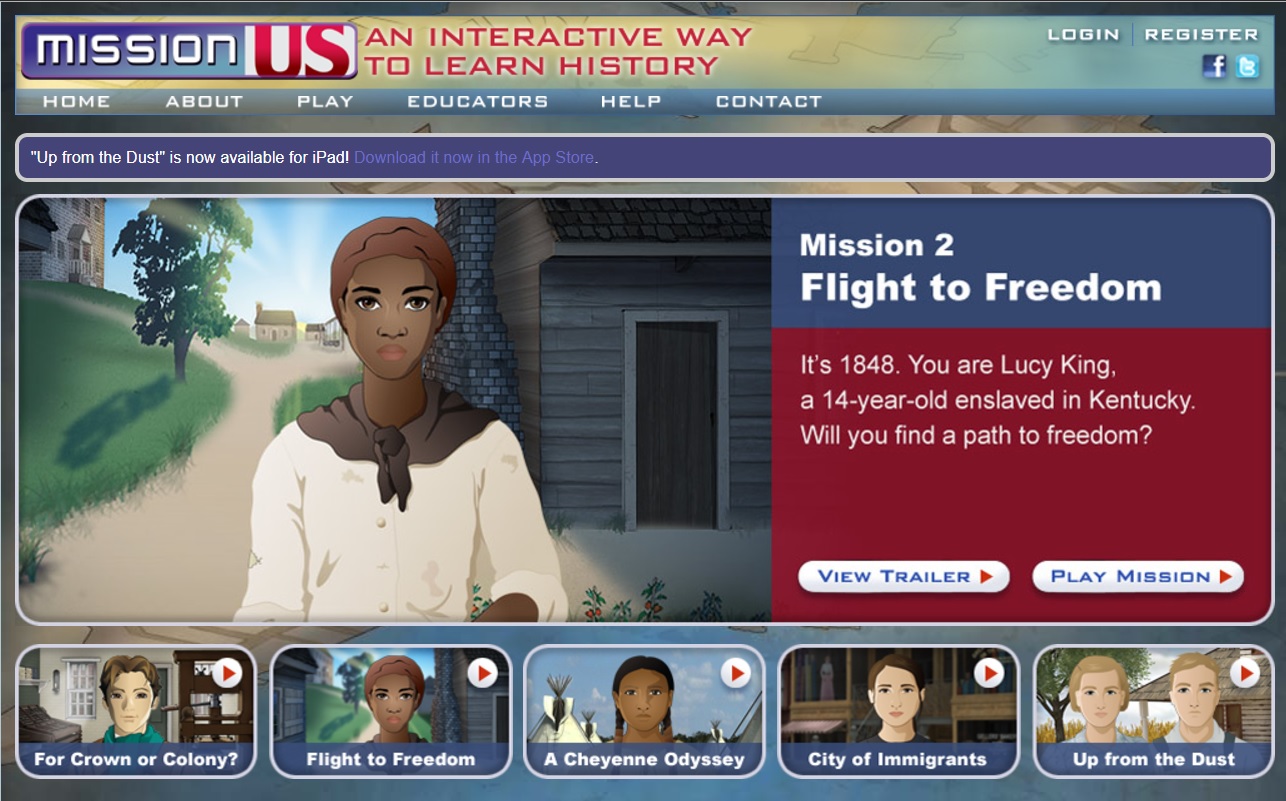

Focus of Evaluation: Mission US: An Interactive Way to Learn History

Project Description

Mission US is an educational, “serious” gaming experience that allows middle school and high school students to immerse themselves in historical environments and conflicts. There are currently four “missions” available to players and the site promises the delivery of a fifth. Mission 1 occurs during the American Revolution, Mission 2 addresses slavery in the United States and the passing of the Fugitive Save Act, Mission 3 covers colonization and the treatment of indigenous peoples, including the Cheyenne, and Mission 4 details the experiences of Russian immigrants and early labor movements in the United States. The purpose of the project is to educate American youth about conflicts in American history, as well as particular historical events. By providing users and players the ability to “experience” conflict in the form of social inequity and struggle, the games and their virtual environments attempt to foster what the creators and collaborators of the project name “historical empathy.” In this way, the games provide an opportunity for students to connect with historical figures on a smaller scale while nurturing the understanding that these occurrences are the result of a larger socio-historical context.

The project was created by Thirteen, a subsidiary of WNET, and is funded through the Corporation for Public Broadcasting with additional funding provided the National Endowment for the Humanities. Educational outreach is sponsored by The Page & Otto Marx, Jr. Foundation and Atran Foundation. Content for each mission is curated by a set of historians that specialize in the respective areas at the American Social History Project/Center for Media & Learning (ASHP), a research center at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Project partners include Chief Dull Knife College, a tribal college, The National Council for the Social Studies, The Freedom Trail Foundation, and the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. Usability testing occurs via the Center for Children and Technology/Education Development Center.

Project’s Relationship to the DH Field

At its best, Mission US’s “Mission 3: A Cheyenne Odyssey” does serve as a kind of cultural repository, particularly in its prologue which is narrated by a speaker of a native language. This marks an important move enabled by DH. In Digital_Humanities, the authors note, “[D]igital networks and media have brought orality back into the mainstream of argumentation after a half-millennium in which it was mostly cast in a supporting role vis-à-vis print…[This] contribute[s] to the resurgence of voice, of gesture, of extemporaneous speaking, of embodied performances of argument” (Burdick et al. 11). Indeed, parts of each of the playable missions offer the opportunity for students to, literally, hear the voices of marginalized communities and a great deal of effort was put forth to create some measure of historical accuracy.

One major issue with this site as a digital humanities project is the lack of transparency in regards to the knowledge design and technical infrastructure. The game is available to both stream and download, free of cost, although both versions require some form of registration and log in. By outsourcing the game programming and design on a contract with the for-profit company Electric Funstuff, Mission US is an especially poignant example of what may happen when we overlap the entrepreneurial space and its tenets with the academic and public broadcasting tradition. In particular, this makes the back-end details of impervious to critique because they are not available for analysis. Even supposed reports of effectiveness by evaluators are only available in short executive summary rather than full empirical study.

“Knowledge Design” Analysis

Burdick and colleagues argue that to push the field of Digital Humanities forward, humanists must now enter the “inside the technology…plunge into the workings of platforms and protocols at least enough to understand how to think critically and imaginatively regarding the tools they employ” (119). The absence of a codex or public documentation of the knowledge design makes much of our critique based on user experience rather than signposted design elements.

When looking at Mission US, we are bridging the analysis of a serious game and understanding the argument made by the modeling of reality inherent in humanities projects. If we utilize the definition of games outlined in Digital_Humanities which includes an ideology of rules, extensive feedback, voluntary play, and delay of gratification, then Mission US fulfills these requirements with slick graphics and engaging story development. It has been described as “fun,” and content knowledge of historical events increased across a large sample size of students in middle and high school. Though those improvements are only reflective of what can be measured by multiple-choice tests, many would ask ‘what more could you want from history class?’ than fun and improving student achievement. Burdick and colleagues, however, would have us take the perspective of engaging in understanding the ideological shape of our digital design, which serves as the base argument being made. In this case, the user experience is built for suburban, white students who need to be “engaged” in history, rather than for a diverse group of students who have formative historical trauma associated with the topics of study. While the game design has the player take on the role of a young person during the historical time period, there is little character development or work required by the player to understand her or his perspective, but rather makes the character a costume for the player. While serious games may be meant to encourage students to “grapple with human experience” (Burdick et al. 52), when it is tied in with the disparity in whom this game seems to be made for versus whose history it ‘gamifies,’ in addition to the badge-based rewards during play, it seems that the ethics of gamifying historical trauma were not deeply considered. For example, a Defiance Badge received by the player character seems flippant when in reality that young girl would have most likely been beaten or worse for defiance. The digital humanists involved here, who have created other DH projects in the past, seem to gloss over the role of affect and the moral requirements of gaming.

Project Critique

In “Venus in Two Acts,” African Americanist Saidiya Hartman issues a call towards narrative practices that both restore the agency and subjectivity of the marginalized voices contained in the archive while respecting the limits of documentation so as not to overly romanticize and thusly partially sanitize the violence enacted upon these marginalized subjects. Hartman asks, “How does one revisit the scene of subjection without replicating the grammar of violence?” (4). Interpreted in a broader sense, Hartman’s work functions to remind us to approach information studies with a critical lens and a staunch set of ethics and self-reflexivity and, ultimately, to understand that in our work, there is the possibility of layering violence upon violence that is, in this contemporary moment, directly linked to historical violences visited upon the lives and bodies of people of color. This is perhaps our biggest worry with regards to Mission US. Is it appropriate for students to earn a “resistance” badge when defying a slave master when we know that black bodies were often mutilated and murdered as an actual response? How does this sanitization of violence instead constitute the re-enactment of violence and erasure that the games promise to productively address? While the games may illustrate an attempt to bridge the distance between historical occurrence and contemporary technology, what does it mean when colonization and indigenous peoples continue to be rendered in a state of “pastness” when colonization is arguably an on-going process, especially for indigenous peoples who continue to exist today? What is the utility of (re)constructing history with digital technology when there is a critical lack of engagement with how white supremacy and colonialism continue to persist in our present moment?